Unveiling Carthage: Beyond Rome’s Shadow

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Those who have a basic understanding of history know the name Carthage. “They had elephants,” some might recall. “There was someone named Hannibal, like in the movie,” others might add. Beyond that, though, most are familiar with this ancient civilization due to its destruction by Rome. However, Carthage was much more significant than a plot point in the first act of Rome’s remarkable saga.

Carthage produced shrewd military minds, cunning politicians, great engineers, and intrepid explorers during nearly 700 years of existence. Carthaginian tactics, methods, and maps also provided great models for success. One could even make the case that not only did Carthage challenge the young Roman Republic but handed future rivals the means for greatness.

The Phoenician Heritage of Carthage

Part of the Carthaginian success story dates back to its origin as a Phoenician colony. With a rich culture and a colorful history, the Phoenicians were a Semitic people with close cultural and political ties to the Ancient Hebrews. Phoenicia was located in the middle eastern region known as the Levant (ca. 3000 BCE). Historians trace its beginnings to an area currently shared by Lebanon, Israel, and Syria. The Phoenician people thrived in the ancient world, earning a reputation as expert sailors and prolific merchants. Their expertise as ship-builders also allowed them to reach further than most of their contemporaries.

Likely with their business ventures in mind, the Phoenicians developed one of the most sophisticated writing systems of the ancient world. The Phoenician alphabet originated from the Canaanite and Aramaic letters and was easier for everyday people to learn and use than other writing systems of the time, such as Egyptian Hieroglyphics or Mesopotamian Cuneiform. Along with other Semitic languages, the Phoenician alphabet also heavily influenced the subsequent Greek and Latin alphabets used throughout the world to this day.

Innovations like these helped the Phoenicians to flourish for the next several millennia. Their strong command of the seas enabled them to continue thriving while their land-bound neighbors languished during the Late Bronze Age Collapse (ca. 1200-1150 BCE). By the eighth century BCE, the Phoenicians were still going strong and competing with the Ancient Greeks for influence over the eastern Mediterranean region. Phoenician cities like Cyprus, Byblos, Sidon, and especially Tyre had developed into commerce and cultural exchange centers. Still, the most impressive city was yet to come. It is here that the story of Carthage begins.

A City Of Refugees

In 814 BCE, a fleet of refugees set sail from Tyre, heading westward across the Mediterranean to the less-developed shores of Numidia (North Africa). They were political exiles fleeing the wrath of a ruthless tyrant called Pygmalion. Commanding this fleet of loyalists was Princess Elissa, Pygmalion’s sister. She was the daughter of Tyre’s late king, Mattan, and the widow of the city’s head priest, Sychaeus. Details are vague, but it seems clear that her brother Pygmalion had usurped their father’s throne, murdered Elissa’s husband, and then robbed her of her inheritance. Elissa and her band of loyalists somehow made their escape and presumably struck out with few resources.

Within the year, Elissa’s ships landed on the shores of what is now Tunisia, a relatively undefined territory at the time. Still, it was surrounded by the established tribal systems of the Berbers (Imazighen). Although they were less sophisticated than the civilizations back east, the local powers would demand tribute from these disadvantaged newcomers if they were to settle there. It was here that Elissa proved herself to be a cunning negotiator.

Using her meager resources, Elissa purchased land from the surrounding leaders with the ambiguous stipulation that it would equate to “whatever an ox hide would cover.” The clever Princess ordered a large ox skin to be shredded into thin strips. Then, she had the pieces strategically placed over enough territory to accommodate a sizeable urban settlement. Her tactic seems to have worked.

Likely out of respect for her shrewd maneuver, Elissa earned a nickname from the local Berbers by which she is better remembered. Princess Elissa became Queen Dido, meaning “the wanderer” (the Greek version of her nickname). Her new city came to be called Qart-Hadasht (New City) or Carthage.

Although they had made a new home, Dido and her people were still vulnerable. They remained submissive to the local powers, leasing the land as a tribute state. Carthage was also technically a colony of Tyre, holding obligations to her powerful mother city. However, this would soon change as the wandering queen and her resilient band of refugees picked a prime piece of real estate. The advantageous location would eventually pay off in a significant way.

An Age of Growth and Change

At first, Carthage was little more than a friendly port for Phoenician sailors to dock, repair, and resupply. However, her status as a hub soon proved to be beneficial. Carthage’s position made for a perfect pitstop between the east-west trade routes along the North African coastline and the north-south trade routes towards the Italian Peninsula. Within a century, the small settlement swelled to a population of around 30,000. Carthage soon grew into a booming city that demanded respect. Her rise was further bolstered by the demise of her masters and competition in the East.

Starting with Dido, Carthage was ruled by a king or queen who would have been the supreme local authority even though they were technically acting as a governor on behalf of Tyre. These rulers were advised by a council of advisors picked from the most elite families of the community. This governing model lasted at least 200 years. Carthage abandoned monarchy two centuries into her existence and joined her Roman and Greek counterparts in experimenting with representative government.

The Carthaginian Republic

During its Republican era, which is often overlooked in the annals of history, Carthage emerged as a fascinating laboratory of democracy and a beacon of innovation. While often overshadowed by the political giants of Athens and Rome, Carthage’s experiments with governance were no less remarkable, offering insights into the evolution of democratic principles in the ancient Mediterranean world.

The Carthaginian Republic, established around the 5th century BC, was characterized by a sophisticated system of governance featuring a bicameral legislature and elected rulers. This arrangement mirrored similar reforms in Athens and Rome but with distinct nuances that set Carthage apart. At the helm of this political structure was the elected Dyarchy, in which two rulers shared executive power. Alongside these rulers was a Senate comprising aristocratic citizens who provided advice and oversight. The Assembly, representing the commoner class, played a crucial role in domestic affairs, debating and approving laws proposed by the higher offices and overseeing the appointment of officials.

What makes Carthage’s democratic model unique is its inclusivity in voting. Unlike Athens or Rome, where only a select few had a voice in governance, Carthage’s system allowed citizens from all social strata to participate in the electoral process. Even the highest offices were open to commoners, albeit indirectly through the Assembly. However, despite this apparent inclusivity, Carthage’s republican model leaned heavily towards oligarchy, with elite families holding sway over higher offices.

Another distinctive feature of Carthaginian governance was the separation of military and civilian politics. While the Suffetes and Senate declared war and the Assembly approved military leaders, civilian interference in military affairs was minimal. A Board of Generals oversaw defense strategies, while a Council of 104 ensured ethical conduct within the military ranks. This clear division between civilian and military spheres contrasted sharply with the entanglement of politics and warfare in Athens and Rome.

Beyond its political achievements, Carthage flourished economically and technologically during its Republican era. Advanced agricultural and fishing techniques ensured food security for its burgeoning population, while urban planning initiatives created efficient, grid-based cities with towering limestone structures and sophisticated plumbing systems. Carthaginian architects, adept at mimicking marble with a stucco-like substance, adorned government districts with grand palaces and temples, showcasing the city’s wealth and ingenuity.

The city’s commercial districts, influenced by its Phoenician roots, became vibrant hubs of trade, attracting merchants from across the Western world. Carthage’s strategic location facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas, fueling economic growth and cultural exchange. This period of prosperity between the 6th and 4th centuries BC witnessed significant expansion for Carthage through exploration and conquest.

An Empire of Commerce

Although technically a Republic, Carthage had its share of great leaders that led them to imperial ambitions. Bold explorers sailed beyond the boundaries of the known world, and cunning tacticians planned the conquest of neighboring lands. All of this was, of course, made possible by Carthage’s Phoenician heritage of maritime engineering.

Hanno the Navigator led expeditions that pushed the boundaries of the known world, venturing as far as modern-day Gabon and encountering phenomena like active volcanoes and African gorillas along the way. These exploratory missions expanded Carthage’s geographical knowledge and facilitated cultural exchange and economic opportunities.

Carthage’s military campaigns, led by generals like Malchus of the Magoanid clan, resulted in significant territorial gains in Western North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and several Mediterranean islands. Despite occasional conflicts, Carthage’s imperial model was characterized by a relatively lenient approach, allowing subject territories to govern themselves while contributing to Carthage’s prosperity through taxes and military support.

The mighty Carthaginian navy, boasting formidable warships like the Quinqueremes, dominated the Mediterranean waves, protecting trade routes and projecting power across the region. Carthage soon put her warships to work, conquering various trade hubs throughout the Mediterranean. However, once conquered, the subjugated cities enjoyed a fair amount of autonomy within the new Empire, which may have been a mimicry of the Persian Achaemenid model. Conquered peoples still maintained their local traditional cultures, governing bodies, and militaries, but now with the protection of Carthage’s warships.

Carthage’s decentralized imperial model was a recipe for success for a long time. Perhaps, in time, she would have followed Rome’s eventual path into despotic rule. Alas, we will never know. Carthage’s prosperity would ultimately attract the envy of her Roman counterparts, leading to a series of conflicts known as the Punic Wars.

Downfall: The Punic Wars with Rome

The Punic Wars between Carthage and the Roman Republic arose from territorial disputes, economic competition, and a general quest for supremacy in the Western Mediterranean. The First Punic War (264–241 BC) erupted over control of Sicily, a strategically vital island that both powers sought to dominate. Rome was only able to rise victorious in this conflict due to a combination of home-court advantage and their copying of Carthage’s naval technology.

The Second Punic War (218–201 BC) was ignited by Carthage’s expansion in the Iberian Peninsula and her desire for revenge. Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca’s audacious invasion of Italy via the Alps nearly brought Rome to its knees, leading to some of the most iconic battles in ancient history. Rome was only able to hold Hannibal at a stalemate for over a decade. Eventually, Roman general Scipio Africanus took the war to Carthage’s doorstep and was able to pull out a victory. Carthage’s vast empire was then absorbed by Rome, leaving her with only the immediate territory around her city walls as a shadow of her former self.

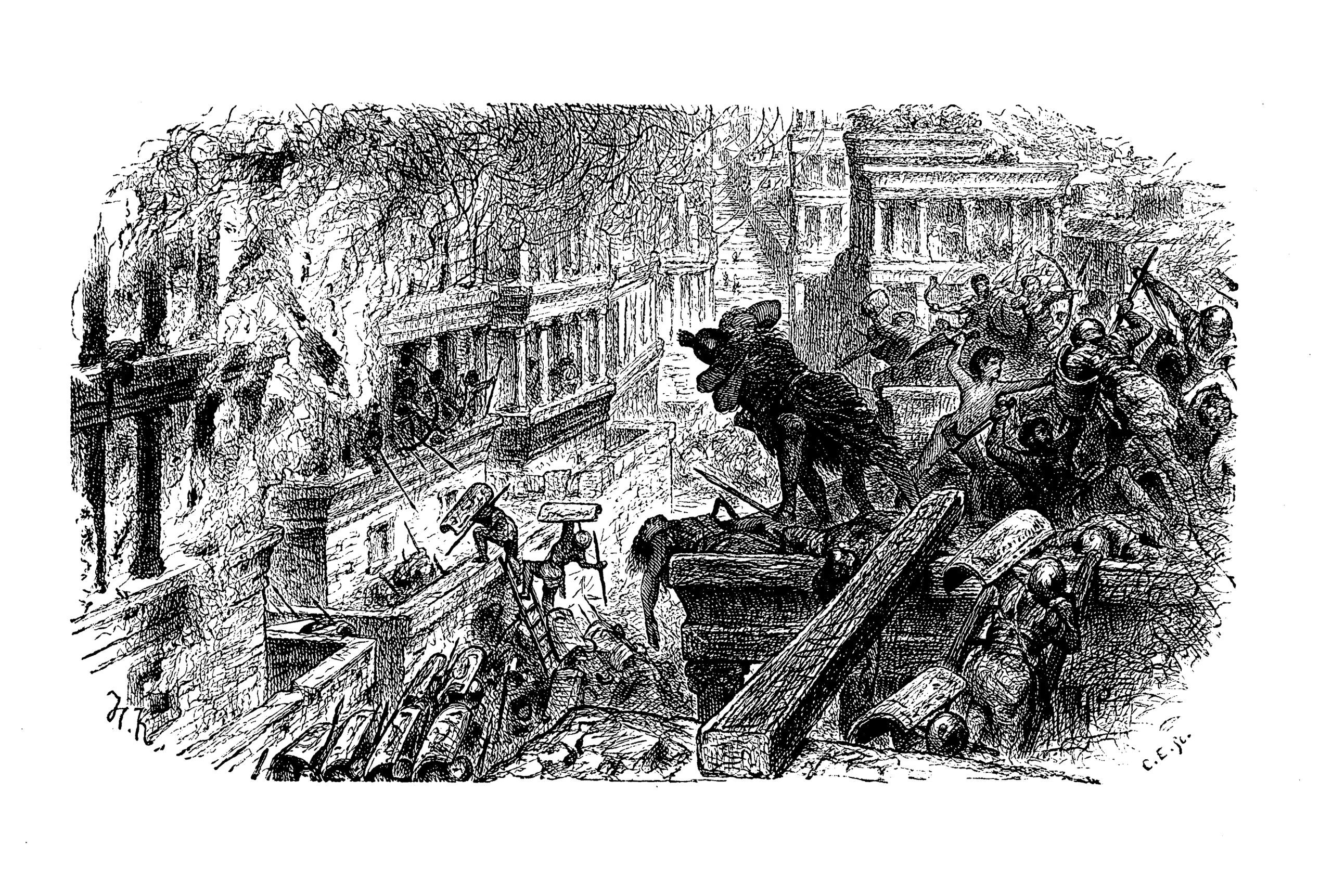

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was driven strictly by Rome’s desire for vengeance and the perceived threat of Carthage’s resurgence. Centuries of animosity between the two ambitious powers boiled over into one final conflict. Despite putting up a formidable defense, Carthage could not withstand Rome’s relentless aggression, resulting in the city’s total destruction. Legend has it that Rome went so far as to sell survivors into slavery, raze the city to its foundations, and salt the earth so that nothing would ever grow there again.

The fall of Carthage marked a turning point in Western history, paving the way for Rome’s unimpeded ascendance as the sole dominant power in the region. However, Rome’s attempts to bury Carthage in the ash heap of history ultimately failed, and her legacy endured. Carthage’s contributions to democracy, urban planning, and naval warfare continue to echo through Western Civilization, demanding recognition alongside its more celebrated counterparts as she continues to shape our understanding of the ancient world.