Olympian Refugees: A Tradition of Peace in a World Divided

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

The Olympic Games have long served a dual purpose. For one thing, they allow individual athletes to compete for the honor of being the world’s best at their sport. They also allow competitors to bring honor to their respective countries by bringing home a gold, silver, or bronze medal. But what about those who find themselves without a country?

At any given moment, millions of refugees, asylum seekers, and other internationally displaced people are fleeing their homelands. They may do so for many life-threatening reasons, including famine, disease, or natural disasters. However, war and persecution remain the most common factors motivating people to brave the odds and the elements in a desperate bid for survival.

In recent years, The Olympic Games have provided an opportunity and an avenue to draw international attention to the plight of refugees worldwide. This makes perfect sense because the Olympics, both Ancient and Modern, have always been an engine for peace and positive change. What started as a happy accident in an ancient corner of the Mediterranean continues to nudge humanity toward a more humane global society.

The Ancient Olympic Games: An Antidote To War

Ancient Greece was not a united nation but a collection of autonomous city-states that shared a common language and general culture. However, even within the more incredible Hellenic culture of Ancient Greece, these cities had laws, customs, and a sense of identity that led them to function like separate countries. This being the case, moments of coming together were rare between cities, certainly rarer than war was. Even so, several Panhellenic (All-Greeks) festivals developed over time. One such festival gave birth to the Olympic Games.

The Ancient Olympics are traditionally understood to have begun in 776 BCE. Because of their mythological origins, they were held at the religious sanctuary of Olympia in honor of Zeus. What may have started as a simple footrace eventually expanded to include other events. Soon, athletes from all over Greece competed in chariot racing, wrestling, boxing, long jumping, javelin, and discus throwing. Unlike today, these ancient games were held annually. Olympia remained the namesake for the event, but the games came to be held in four different regions. Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia sequentially hosted the games over the four-year Olympiad cycle to ensure all eligible athletes had a chance to participate.

As per the culture of the time, the competitors were male. Women could be represented vicariously by sponsoring a man to compete on her behalf. Still, Hellenic gender norms decreed sports were strictly a masculine activity. This connection to Hellenic manhood was also the most significant factor in the popularity of the games. The Ancient Greek concept of Arete was central to one’s identity within Hellenic culture. Sometimes translated simply as “Excellence,” Arete refers more precisely to one’s “best self.” Ancient Greeks, especially men, sought to become the best possible version of themselves, with their success measured primarily by reputation.

Before the Olympics, Greek men looked to ancient Homeric epics like The Iliad, and sought recognition through bravery on the battlefield in imitation of heroes such as Achilles. However, once the Olympics were introduced, athletic competitions offered a non-lethal venue for men to demonstrate their abilities. By winning a gold, silver, or bronze medal, competitors gained glory and respect for themselves and their cities. Athleticism supplanted warfare as Greek men now had role models in the form of Olympic champions. As such, the growing popularity of the Olympic Games correlated with a distinct decline in warfare between cities.

The games proved crucial enough that a Sacred Truce was arranged to continue even during significant conflicts like the Greco-Persian War (499-449 BCE) and the Peloponnesian War (424–404 BCE). Eventually, eligibility to compete was extended beyond free-born Greek male citizens to citizens of the Roman Empire and then eventually to anyone who spoke Greek. However, despite a long history and being a catalyst for peace, the Roman Emperor Theodosius outlawed the Olympics in 393 CE for religious reasons.

The Modern Olympics: Diplomacy Through Athleticism

Centuries after the ancient games were banned, there were sporadic attempts to revive them. Motives ranged from foreign fascination to Greek nationalism, but Baron Pierre de Coubertin’s vision for a better world prevailed. De Coubertin lived through France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, followed by a revolution and continuous social unrest. Amid this, he pursued a life of intellectualism and developed a passion for classical Greece and educational theory. All this eventually culminated in an optimistic ideology.

De Coubertin observed that organized sports in English schools fostered moral and social strength, balanced mind and body, and kept youth-focused. He believed the ancient Greek approach to education, emphasizing physical and intellectual development, had been forgotten and dedicated his life to its revival. His romanticization of ancient Greece led him to advocate for integrating these principles into modern schools.

While Coubertin idealized Ancient Greece, his push for physical education had practical roots. He believed physically trained men made better soldiers. He also saw sports as a democratic activity, crossing class lines without mingling them. After failing to increase physical education in French schools, de Coubertin shifted his focus to something more ambitious: reviving the Olympic Games.

De Coubertin’s advocacy for the Olympics was grounded in several ideals. He valued amateur competition and believed the Sacred Truce associated with the ancient games could promote modern peace. He saw athletic competition as a means to foster cultural understanding, reducing the risk of conflict. For Coubertin, the essence of the Olympics was not found in winning a medal but in the struggle and effort of the competition.

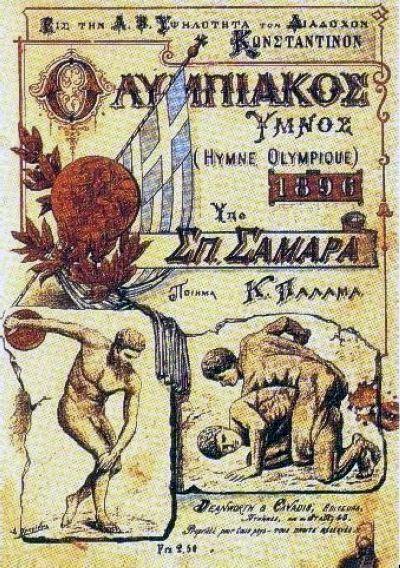

De Coubertin became the driving force behind organizing the first Olympic Committee, which laid the foundation for the modern Olympic Games. In 1894, he convened a congress at the Sorbonne in Paris, gathering international representatives to discuss reviving the Olympics. His efforts led to the establishment of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), which was crucial in planning the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. This event marked the beginning of today’s international sporting tradition, with the division between Summer and Winter sessions added in 1924.

One might say that de Coubertin’s hopes for the effect of athletic diplomacy and the Sacred Truce were overly optimistic, given how history has unfolded. The modern Olympics have not disrupted wars but instead faced disruptions themselves in the face of global conflicts. The 1916, 1940, and 1944 games were canceled due to the World Wars. During the Cold War, large-scale boycotts in 1980 and 1984 led to limited participation. The games were also targets of terrorist attacks in 1972, 1996, and 2008. Also, geopolitical issues affected many athletes’ eligibility to compete. As early as the 1940s, hopeful athletes from numerous countries were denied entry, a problem that persisted through the 1970s. Even so, a silver lining emerged in what happened next.

Independent Olympic Teams

As the 1980s approached, discussions occurred about separating athletes from their native countries’ political issues. The IOC introduced the idea of Independent Olympic Athletes Teams. Athletes could now be considered for participation without representing certain ineligible nations. These teams and athletes would compete under the Olympic flag, and the Olympic Anthem would be played for them during medal ceremonies if they triumphed.

The new policy went into effect in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, welcoming athletes from Western Europe who wanted to compete despite their governments’ support for a boycott inspired by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. A second notable example occurred during the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona when 58 athletes from Yugoslavia and Macedonia competed as independent participants, winning three medals. For various reasons, the 2000, 2012, and 2014 Olympics also included athletes competing as independents. Then, in 2015, a global crisis occurred.

In 2014, several conflicts erupted in the Middle East in the form of civil wars in Syria and Libya, as well as an insurgent war in Iraq. Their own domestic turmoil also affected adjacent areas in North Africa and Eastern Europe. Within a year, over a million refugees were driven from their native lands. Most went westward, taking treacherous paths across land and sea, to seek asylum in the European Union. European nations were unprepared for the influx of refugees. Still, Germany, France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom eventually rose to answer the call for shelter.

Among this multitude of refugees were many amazing athletes. The IOC took notice of this and acted accordingly. In March 2016, IOC President Thomas Bach – whose native Germany was quickest to open its doors to the displaced masses – announced that in recognition of the global crisis unfolding, 5-10 refugee athletes would be selected to compete in the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. In addition, the United Nations Refugee Agency chose Ibrahim Al-Hussein, a Syrian refugee, to carry the Olympic flame through the Eleonas refugee camp during the torch relay.

Olympics For All!

Initially called the “Team of Refugee Olympic Athletes,” the team was soon renamed the Refugee Olympic Team (ROT) in June 2016. The athletes competed under the Olympic Flag, just as their independent predecessors had done since 1980. The team comprised exiled athletes from South Sudan, Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ethiopia. Some of them, such as Yusra Mardini of Syria, had been training vigorously to represent their countries before being forced to flee. While most ROT athletes competed in Athletics, Mardini stood out as a swimmer. Popole Misenga and Yolande Mabika, both Congolese, also stood out by competing in Judo.

While the ROT received no medals, their impressive performances and harrowing stories drew international intrigue. Most notable is probably Mardini, who was only 18 at the time. Her flight from Syria and its ensuing civil war in 2015 included her crossing the Aegean Sea in a small raft with other refugees. When the craft threatened to sink, Mardini and her sister Sara (also a trained swimmer) heroically leaped from the craft to lighten the load. The two young women swam beside the tiny raft for many leagues of treacherous waters. Their journey inspired the Netflix original movie The Swimmers (2022).

Mardini’s fellow Syrian and swimmer, Rami Anis, was also an asylum seeker driven from his home by the Syrian Civil War. This conflict was the primary generator of the wave of refugees that grabbed international attention in 2015 and inspired the inclusion of the ROT. Be this as it may, Mardini and Anis were the only two refugees displaced by that war or any conflict that contributed to the 2015 Refugee Crisis. The rest of the team had been displaced for years by disputes such as the Second Congo War (1998-2003), the Second Sudanese Civil War(1983-2005), and general ongoing persecution in Ethiopia. This comes as no surprise when one considers that the United Nations reported an estimated 82 million people living as refugees worldwide, which has risen to over 117 million as of 2023.

The Olympic Refugee Foundation (ORF) was established in 2017 to support displaced and refugee athletes worldwide. The foundation was born from the IOC’s commitment to using sport to bring hope and inclusion to refugees. The ORF collaborates with various partners, including governments, NGOs, and the United Nations, to create safe sports programs and facilities in refugee camps and communities affected by displacement.

Since the ROT’s debut in 2016 and the ORF’s creation the following year, refugee athletes have continued participating in the Olympic Games under the Refugee Olympic Team. The presence of refugee athletes was solidified at the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, where 29 athletes from 11 countries competed in various sports to represent the millions displaced by conflict and persecution. The 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, France, saw an ROT team comprised of 37 athletes from 11 countries of origin, although most hailed from Iran. These athletes competed in 12 sports. Cindy Ngamba of Cameroon won a bronze medal in boxing to become the first-ever Olympian to win a trophy for the ROT.

Passing The Torch

Perhaps de Coubertin’s dreams of the power of the Sacred Truce to halt war did fall short of reality. However, even the Ancient Olympic Games could not stop war altogether. Also, despite the occasional sporadic challenges the Olympics of recent centuries have faced, a silver lining has undoubtedly shown. The Olympics have brought attention to athletes affected by conflict and persecution. This, in turn, has drawn, and continues to draw, attention to the affected people they represent.

By creating a category for athletes without a country to compete on the world stage, the Olympics have given a home to people experiencing homelessness. The ROT remains a symbol of resilience and the unifying power of sports in general and the Olympics specifically. The ORF’s ongoing work ensures that the spirit of the Olympics extends beyond the Games, providing opportunities and hope to those in the most vulnerable situations.

Perhaps athletic diplomacy cannot end all wars. However, it has proven that it can champion the cause of those affected and displaced by war. The Olympics accomplishes this by creating champions from among these same displaced individuals. Who knows? Perhaps, just as it was in antiquity, these new role models will pass the torch to future generations and inspire a better world.