The Timeless Lessons of “The Lord of the Rings”

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

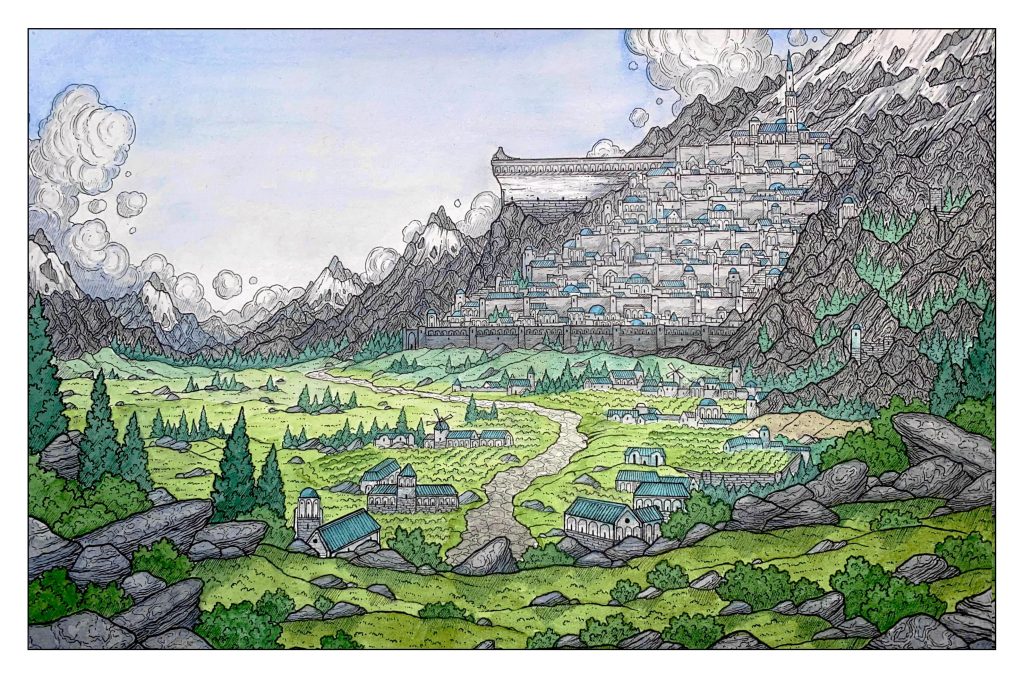

For nearly a century, countless readers and viewers have found refuge in the enchantment of Middle-earth—a fantastical realm filled with magic, courage, and resilience. Crafted by the meticulous hand of linguistic scholar and World War I veteran John Ronald Reul Tolkien, Middle-earth first emerged in The Hobbit (1937) and later in The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955). A detailed backstory for the fictional world was laid out in The Silmarillion (1977) after the author’s death, and many more unfinished stories hint at what adventures might have lay ahead. One might wonder what makes these stories resonate so deeply with audiences. Perhaps their staying power is their timeless and surprisingly progressive themes. These themes grow more poignant as other elements of Tolkien’s storytelling have become dated, proving that light can endure, even in the darkest of places.

“Showing its Age” vs “Aging Badly”: An Answer to Modern Critics

As younger generations reexamine the world, some decry Middle-earth’s lore as racist or bigoted. Identifying flaws in past societal standards is a healthy process that keeps us moving toward a brighter future. However, labeling all these shortcomings as villainous ignores the nuances of history, and overlooks the stepping stones of past progress.

Some aspects of Tolkien’s original works are undeniably dated. But an important difference exists between a story “showing its age” and a story “aging poorly.” Tolkien’s work may bear some outdated norms and views of his generation, but does this diminish the power of its positive messages?

The answer is that all stories show their age at some point by displaying both positive and negative tendencies of their time. They cannot help but reflect the world as it was when they were first composed, warts and all. On the other hand, a story that has aged poorly displays, and even endorses, the worst tendencies of its time. It is all warts and nothing more. It is in this inherent duality that the timeless stories transcend their origins. In this light, one might argue that Tolkien’s works, and Lord of the Rings in Particular, has aged rather well.

The Origins of Tolkien and Middle-Earth

Tolkien was born in South Africa to English parents, but his connection to his birth country was quite minimal. He left for England at age three after his father’s death and never returned. Following the death of his mother 9 years later, Tolkien was raised by Father Francis Xavier Morgan, a Catholic priest and family friend. Father Morgan ensured the young man received a proper British education with staunch Catholic guidance. Tolkien went on to study literature and language, served on the front lines of WWI, and then contributed to the Oxford English Dictionary before becoming a Professor of Literature. Eventually, he turned to fiction writing as a creative outlet.

Tolkien’s goal in creating Middle-earth was primarily to craft a mythology for England. Works like Beowulf and The Wanderer offered glimpses of Anglo-Saxon mythology, but much of that tradition had been lost or diluted by external influences. The Legend of King Arthur has significant French origins, and most other “English” myths tend to draw from Scandinavian or Celtic roots. Tolkien could not rewrite history, but endeavored to write something new to fill the cultural void.

Another criticism is that stories like these are inherently ethnocentric. In this respect, one has to admit Tolkien’s fairytale landscape is rather mono-ethnic and populated by characters resembling white Europeans. However, this was not done with malicious intent, it was a matter of art reflecting life. Both the medieval texts Tolkien drew inspiration from and the England of his generation were not very culturally diverse, unlike the UK of today.

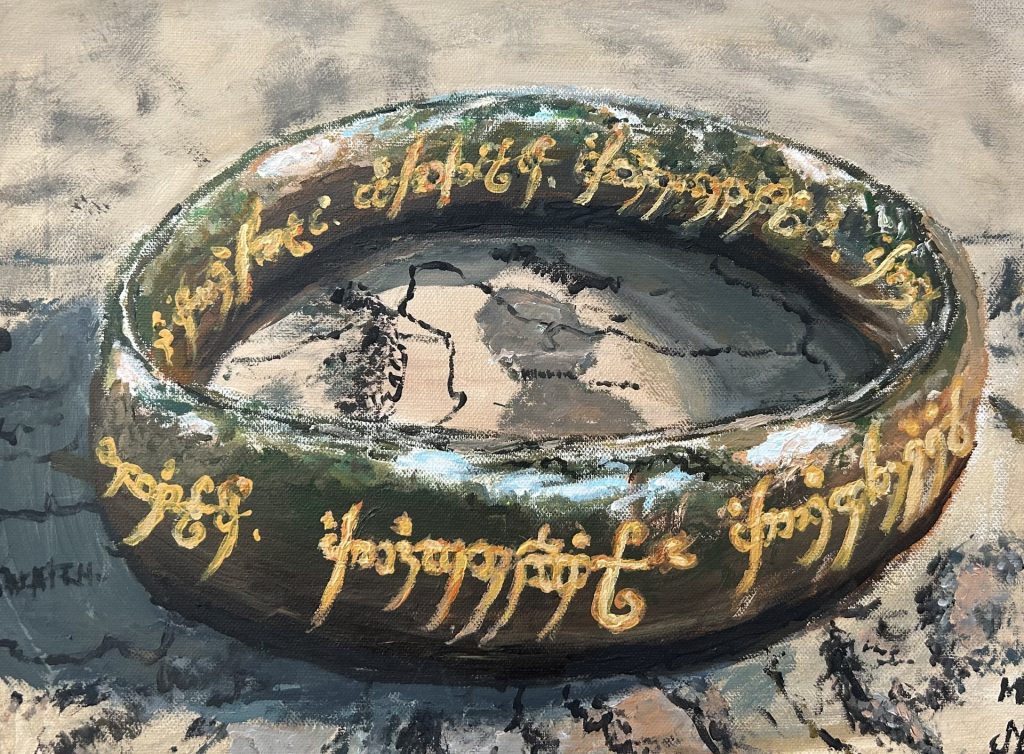

Another factor that raises eyebrows is that Tolkien also drew clear inspiration from the works of Richard Wagner, a composer remembered today for his antisemitism and staunch atheism. Some misguided critics (and even fans!) often miss the fact that Tolkien took great care here to separate the art from the artist, recognizing a good story buried within problematic beliefs. Being both a devout Catholic and anti-fascist, Tolkien reimagined Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelung through The Lord of the Rings, stripping away the composer’s bleaker messaging in favor of themes of hope and unity that still resonate today.

There is Strength in Diversity

Middle-earth is home to a plethora of diverse races, defined not by the color of their skin but by their stature, longevity of life, and certain other features. Noble Elves, valiant Men, industrious Dwarves, and humble Hobbits all populate the landscape. The evil that threatens them can be held at bay only through the cooperation and unity of these distinct groups. This is especially evident in the Fellowship of the Ring, which consists of members from all corners of Middle-earth. The strength to fight the great evil of Sauron and Mordor is only found in the combined power of these cultures working together.

The personal growth of Gimli the Dwarf and Legolas the Elf throughout the trilogy poignantly champions the overcoming of historical and personal prejudice. Initially, both characters view each other’s races with disdain—Gimli sees Elves as arrogant and aloof, while Legolas regards Dwarves as stubborn and unrefined. Yet, as they travel and fight together, a bond grows between them. Soon, they laugh and joke in the heat of battle, coming to understand and respect one another. In the final battle together, the two have a significant exchange in which they recognize they are not fighting side by side as an “elf” or “dwarf” but as “friends.”

Evil Corrupts, But Redemption is Possible

For Tolkien, evil was corruptive force, not inherent trait, and therefore something that could be healed. Tolkien’s treatment of Middle-earth’s “evil races” also carries a subtle but important message about trauma and corruption. Orcs, for instance, are not born as evil creatures, but are twisted and deformed, from a legacy of corruption and torture. Gollum/Smeagol is another antagonist who suffers from the trauma of a corruptive influence. Although no orcs defect from Mordor and Gollum ultimately succumbs to his addiction, Tolkien hints that redemption is a possibility for any and all.

The same may be said of the human races who side with Mordor. Many of these peoples have an Eastern appearances, which some have interpreted as an example of veiled racism. Again, though, one must also consider the sources from which Tolkien drew inspiration. Throughout the Middle Ages, Europe was repeatedly invaded by aggressive eastern cultures, including Huns, Magyars, Turks, and Mongols. Therefore, fiction mimics these historical anxieties. Worthy of note, though, is that Tolkien’s lesser-known writings hint that these peoples were actually divided about serving Sauron. Again, this is because evil corrupts the individual, and is not inherent to race.

Tolkien’s Positive Masculinity

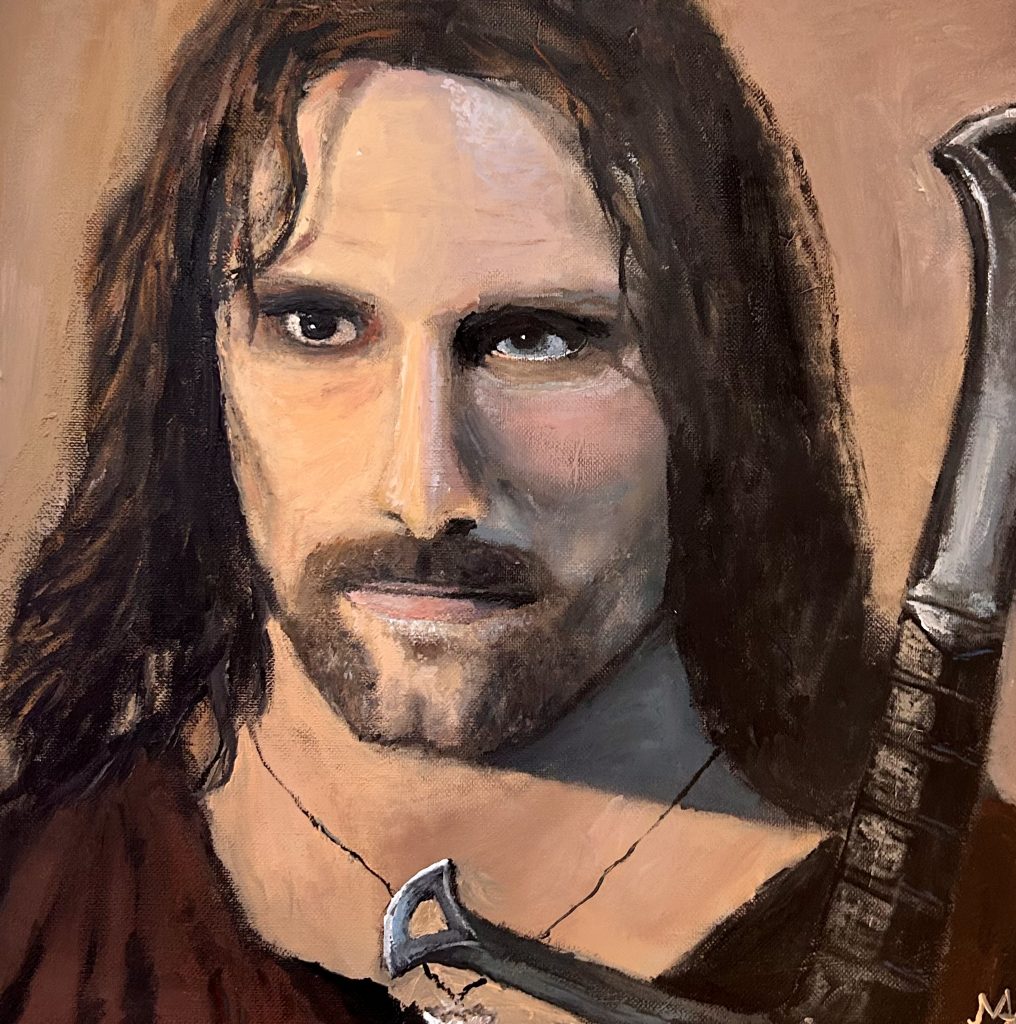

Tolkien offers a rich exploration of what it means to be a man. Heroes like Aragorn, Frodo, and Samwise offer a refreshing perspective on masculinity that embraces trust, vulnerability, and compassion. Tolkien’s leading men are not afraid to express emotion. They trust and talk about their feelings, offer one another support, and show tenderness in times of great distress. These relationships are defined by mutual respect, love, and loyalty, with the common goal of defending those weaker than them.

In a story almost devoid of sexual content, Lord of the Rings in particular focuses on the deeper emotional bonds between characters. One result of this is an absence of homophobia, which allows fraternal love and friendship to shine through in their purest forms. These themes and characters provide a powerful contrast to many stereotypes that often dominate portrayals of manhood.

Ableism and Sexism: The Real “Myths”

The Lord of the Rings is a predominantly male-driven story and thus often critiqued for its minimal portrayal of female characters. Once again, his portrayal of gender roles is consistent with the medieval myths from which inspired him and with the views of his own culture and generation. Still, even within these limitations, Tolkien provides us with Éowyn of Rohan, who defies expectations and takes up arms to protect her people.

Some view Éowyn’s role as an example of “tokenism” (which tempts a pun), but her significance in the narrative is undeniable. She is arguably as deep a character as most of the men, and she embodies female agency in a world that sidelines women. It is Éowyn, after all, who stands up to and defeats The Witch King of Agnar that “no man can kill.” Tolkien really did not need to include her at all to sell books in his own time, but he chose to do so anyway. His choice left a foundation of female empowerment for future fantasists to build upon.

Tolkien furthermore challenged ableism by portraying the miniature Hobbits as his main protagonists. Often dismissed or mocked for their small size and seemingly insignificant nature, Hobbits end up being the pivotal heroes who ultimately save Middle-earth. Despite their lack of conventional strength, Frodo, Sam, Merry, and Pippin display tremendous courage and resilience, ultimately playing key roles in the triumph of good over evil. Such storylines challenge the idea that gender or physical prowess determines a person’s worth. In the end, only we can do that for ourselves.

Finding Your Courage: Overcoming Imposter Syndrome

Another predominant theme throughout Tolkien’s work is overcoming self-doubt. This is best shown in the character arc of King Théoden, whose struggle serves as a powerful metaphor for anyone struggling with imposter syndrome. When we first meet Théoden, he is a withered and broken man manipulated by dark magic through the toxic advice of Grima Wormtongue. Even after the spell is broken, Théoden is still plagued by lingering feelings of unworthiness regarding his ability to lead.

However, as the story progresses, Théoden finds his courage and overcomes his fears, embracing his true role as a King. Théoden’s journey shows that self-worth does not come from external validation but from recognizing one’s inherent value and capacity to rise to the occasion. In the end, imposter syndrome is really just a cruel illusion.

Environmental Consciousness

Another enduring message in Tolkien’s work is his concern for the environment, particularly in the face of industrialization. The juxtaposition of the natural world and industrial progress is vividly represented in the contrast between the peaceful Shire and the blight of Saruman’s Isengard. Saruman’s lust for power and control leads him to deforest large swaths of the land to fuel his war machine, an act that represents the evils of unchecked exploitation of nature.

This reflects Tolkien’s own concerns about industrialization’s encroachment and the loss of connection to the natural world. The beauty of nature—represented by the lush forests of Lothlórien and the rolling hills of the Shire—serves as a counterpoint to industrialization’s destructive forces, reminding readers of the importance of preserving the environment.

What Really Matters in Life

Amidst the epic battles and grand quests, The Lord of the Rings subtly emphasizes the importance of the simple joys of life. This sentiment echoes Tolkien’s own experiences as a veteran, where the horrors of war instilled in him a deep appreciation for the small, everyday moments of happiness. In contrast, the pursuit of power and wealth is shown to be hollow. Those who chase after their own ambition are ultimately undone by it.

The true riches of life lie in the simple repose that brings warmth and comfort. After all the battles have been fought, the smell of roasting potatoes, the warmth of a hearth, and the comfort of a good book offer the true peace that makes life worth living. One could do worse, then, to open a book penned by Tolkien and take refuge in the heart of Middle-earth.

Adapting Adaptations: Middle Earth’s Evolving Portrayal on Screen

Although beloved by fans, Tolkien’s books initially found a niche audience due to their dense, prose. Still, Tolkien’s influence was undeniable as authors like David Eddings, Lloyd Alexander, and Terry Brooks drew heavily from his template. Some animated adaptations of Tolkien’s works in the 1970s and 1980s were met with mixed reception. Then everything changed with Peter Jackson’s groundbreaking Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001–2003). Jackson’s first’ films not only captured Tolkien’s vision but also expanded his audience, ushering in a cinematic fantasy renaissance.

Jackson took great care to stay true to Tolkien’s vision and change only what was necessary. As such, Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy featured a predominantly Eurocentric cast. As the journey continued with The Hobbit Trilogy (2012–2014), Jackson showed sensitivity to modern audiences by incorporating more diverse casting including an original female lead and more people of color. Subsequent adaptations of Tolkien’s work, like Amazon’s The Rings of Power (2022), have taken even greater care to portray a diverse Middle-earth that all audiences can connect with. Now, with War of the Rohirrim (2024), and even more films planned for 2026, It seems clear that Middle-earth’s enduring appeal, like its positive messages, show no signs of waning.