Tattoos—from Tribal to Viral

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

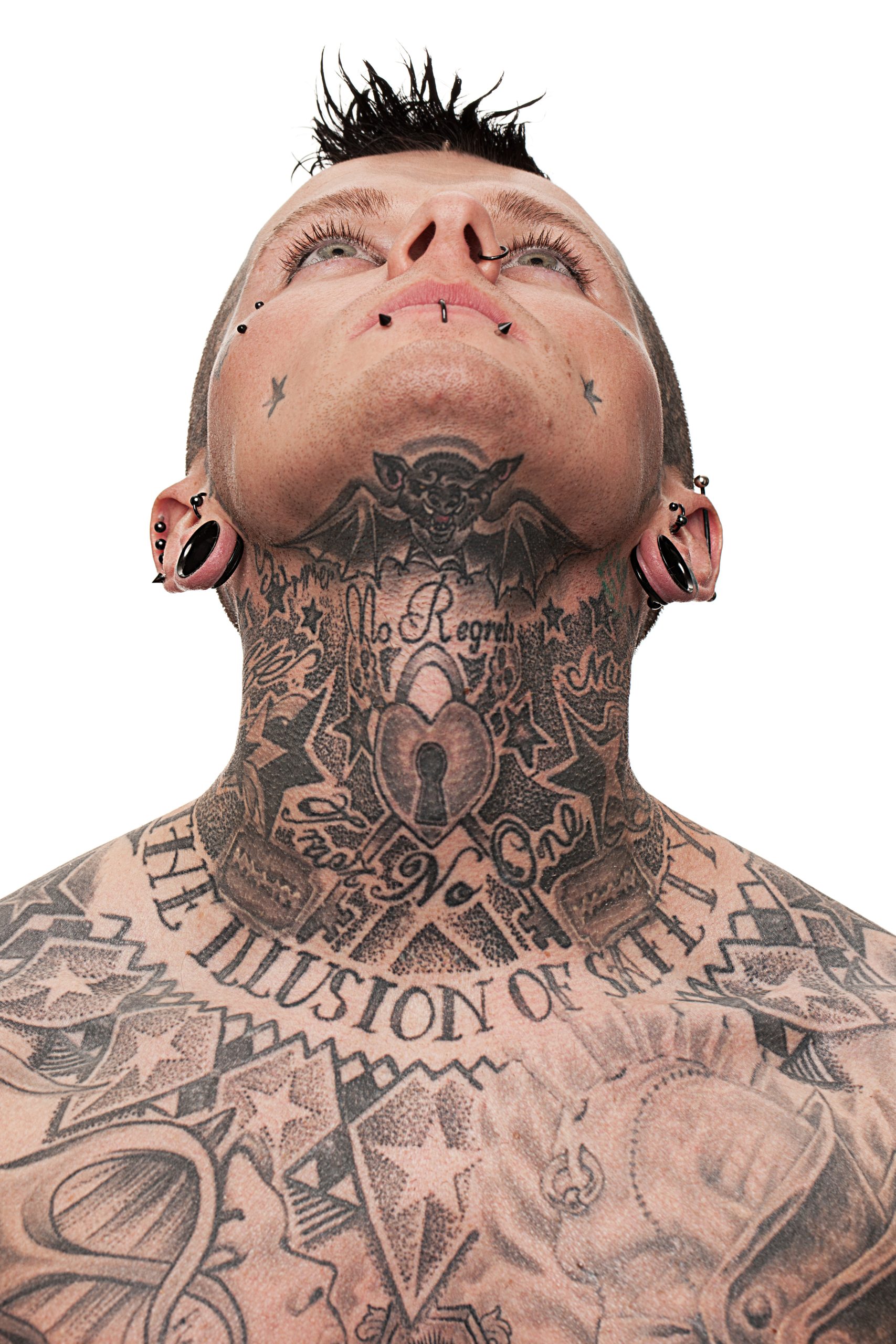

Do you have tattoos? If not, chances are you know someone who does. While tattoos are ubiquitous today, humans have adorned our bodies with symbols and images since ancient times. Although the tattoo machine is a late 19th-century invention, the art of creating images by injecting ink into the mid-layer of the skin has been practiced for thousands of years. Disparate civilizations and cultures around the globe are linked by an inky meridian giving visual expression to primal needs.

These cross-cultural needs are represented by amulets, marks of status, declarations of passion, religious symbols, and even punishments. Tattooing methods and styles have evolved over centuries, but whether simple or elaborate, a tattoo embodies permanence. How did this ancient, deeply personal rite become part of mainstream culture? Let’s explore the broad cultural significance of the oldest form of body art.

An Art as Old as Humanity

Permanent forms of body art are seen in different cultures all over the world. At a tribal level, tattoos may indicate age, marital status, power, and class—the oldest evidence of tattooing dates to around 3300 BC. They may distinguish friends from foes. In many tribes, women’s tattoos were symbols of beauty that also made them less attractive to neighboring tribes. Tattoos seem to have spread with the migration of nomadic people; women in gypsy tribes from India and the Middle East were tattoo specialists.

Traditionally, tattoos were applied as marks of distinction, awarded for achievement, or to signify the transition to adulthood. Pain and blood are unavoidable aspects of tattooing; in many cultures, this endurance is intrinsic to initiation ceremonies. The art has been practiced globally since at least Neolithic times, as evidenced by mummified skin, ancient art, and archaeological records.

Tattooing was a sacred event involving rituals to ancestral spirits and the heeding of omens. For example, if the artist or the recipient sneezed before tattooing, it meant the spirits disapproved, and the session was called off or rescheduled. The artists were usually paid with livestock, heirloom beads, or precious metals, and the recipient’s family often housed and fed them while they worked. Tattoos were acquired gradually over the years, and a design could take months to complete and heal before a celebration was held to honor its completion.

Ancient tattooing was most widely practiced among the Austronesian people of South East Asia. It was one of the early technologies developed by the Pre-Austronesians in Taiwan and coastal South China by at least 1500 BCE, before the Austronesian expansion into the islands of the Indo-Pacific. Ancient tattooing traditions have also been documented among Papuans and Melanesians, using distinctive obsidian skin piercers.

Tattoos dating back as far as 6000 BC were discovered on an Egyptian mummy. In 1991 Otzi the iceman was found preserved in a glacier on the border of Austria and Italy. He had fifty-seven tattoos! Carbon dating revealed that he was at least 5,300 years old. The placement of the tattoos suggests they may have been used for therapeutic purposes rather than aesthetics, as they mark known acupuncture points for stomach and back pain. An analysis of the corpse indicated that it was likely that Ötzi suffered from joint, back, and stomach pain while he lived. Before the discovery of Ötzi, the oldest human remains to show, evidence of tattoos was from the Egyptians in the age of the pyramids about 4,000 years ago.

Tattoos were symbols of tribal identity, kinship, bravery, beauty, and social status that could document personal or communal history. They were also believed to have magical properties and ward off evil spirits. Their design and placement varied by ethnic group, affiliation, status, and gender. This ranged from almost covering the body, including tattoos on the face meant to evoke frightening masks among the elite warriors of the Visayans, to being restricted only to certain areas of the body like Manobo tattoos that were only inked on the forearms, lower abdomen, back, breasts, and ankles.

Ancient Tattoo Techniques

Tattoos were inked by skilled artists in current-day Indonesia using the distinctively Austronesian hafted tattooing technique. This involves using a small hammer to tap the tattooing needle or a group of needles inset perpendicular to a wooden handle. The handle gave the needle stability and made it easier to maneuver while tapping moved it rapidly in and out of the skin.

The needles were made from wood, horn, bone, ivory, metal, bamboo, or citrus thorns. The points created wounds that were then rubbed with ink made from soot or ashes mixed with water, oil, plant extracts, or even pig bile. Tattoos were almost always monochrome, and that usually meant black.

The artist commonly traced an outline of the designs on the skin with the ink, using pieces of string or grass, before tattooing. Sometimes, the ink was applied before the tattoo points were driven into the skin. Most tattoo artists were men, though female practitioners also existed. Some villages had their own artists, while itinerant artists plied their trade moving between villages.

Another tattooing technique predominantly practiced by the Lumad and Negrito people (from current-day Philippines) used a small knife or a hafted chisel to incise the skin in small dashes. These wounds were then rubbed with pigment. This differed from the techniques that used points as the process produced scarification, although motifs and placements were similar to tattoos made with hafted needles.

Around the Ancient World

Regardless of where and when tattoos originated, they have played a significant role in cultures throughout history, with uses as opposite as spiritual symbols or marking enslaved people and criminals.

Indigenous people of North America have a long history of tattooing. For them, tattooing was a process that emphasized cultural connections to indigenous ways of knowing and considering the world, as well as links to family, society, and place. They inked with extreme pain, and the tools used for this purpose were needles, sharp awls, or piercing thorns that perforate the skin before outlining the fresh bloody design, with powdered charcoal or other pigments mixed with the blood to penetrate within the perforations.

The Inuit have a rich history of tattooing. Among the Inuit, some tattooed female faces and body parts symbolize a girl transitioning into a woman and signify the start of her first menstrual cycle. They believed the tattoo represented a woman’s beauty, strength, and maturity. This was important to their tradition since they thought women could only transition into the spirit world with tattoos. The older generation of Inuit recalls how the tattooing was done during their time, using a needle and thread and sewing the tattoo into the skin by dipping the thread in soot or seal oil and through the skin using a sharp needle.

The Osage people used tattoos for a variety of distinct reasons. Their designs were based on the belief that people were part of the larger cycle of life and integrated elements of the land, sky, water, and the space in between to imply these beliefs. Osage men were often tattooed after completing major feats in battle as a visual and physical reminder of their raised status in their community. The women were tattooed in public as a form of prayer, demonstrating strength and dedication to their nation.

In Japan, tattooing is thought to go back to the Paleolithic era. Originally tattooing in Japan was done for spiritual or decorative purposes. However, by the 1600s, tattoos were associated mainly only with the ‘floating world’ subculture, consisting of manual workers, firemen, and prostitutes. Hence tattoos were prohibited entirely by 1868, leaving them to become a mark of criminals and outcasts, and their eventual adoption by the Japanese mafia known as the Yakuza.

The Igorot people of the Philippines have left mummies with highly individualized tattoos covering the arms of female adults and the whole body of adult males in various burial caves in northern Luzon, with the oldest examples dating back to the 13th century.

The Visayans, also known as Pintados, saw inking as a mark of nobility and bravery. They tattooed the whole body from head to toe when they were of an age and strength sufficient to endure the considerable pain. Their bodies were pricked and marked until blood was drawn. Powder or soot made from pine resin, which never faded, was applied. The men tattooed their faces, simulating a mask. Children were not tattooed, and women tattooed only on their hands.

In ancient China, tattoos were considered a barbaric practice associated with the Yue peoples of southeastern and southern China. Tattoos were often referred to in literature depicting bandits and folk heroes.

The ancient Greeks and Romans used tattooing to penalize enslaved people, criminals, and prisoners of war. Ancient Egyptians and Indians used tattoos as healing aids and symbols of religious worship. Tattooed Egyptian mummies—primarily female—have been uncovered dating back to the pyramids.

Māori women from New Zealand were tattooed on their faces with markings that tended to be concentrated around the nose and lips. Although Christian missionaries tried to stop this tradition, the women kept it up. They claimed tattoos around their mouths and chins deterred the skin from wrinkling, keeping them young. The practice continued up to the 1970s and is currently undergoing a revival.

As Western colonizers pushed into places like Africa, the Pacific Islands, and North and South America in the 1400s and 1500s, they found entire groups of native peoples who were tattooed. These tattooed individuals were often pointed to as proof that the ‘untamed natives’ needed the help of ‘good, God-fearing’ Europeans to become fully human. Tattooed individuals from these cultures were brought back and paraded through Europe for profit.

In Europe, as Christianity emerged, tattooing was considered a barbaric tradition and declined, becoming the preserve of sailors and the lower classes. Later, as tattoo artists became more proficient, tattooing became fashionable among the aristocracy for a while. Then as tattooing became cheaper, it was again seen as a mark of the lower classes until the 1960s and the hippie movement, when it slowly entered the mainstream, changing from deviant behavior to acceptable self-expression.

The Height of Fashion

By the 19th century, tattooing had spread across British society but was still primarily associated with sailors and the criminal classes. Tattooing had, however, also been practiced in an amateur way by public schoolboys from at least the 1840s. By the 1870s, it had become fashionable among some members of the upper classes, including royalty. It could be a lengthy, expensive, and sometimes painful process in its upmarket form.

The introduction of tattoos to the western world is often credited to Captain James Cook’s voyages in the South Pacific in the 1770s, which brought tattooing into the public eye. In the late 19th century, tattooed ladies started appearing in circus sideshows throughout the US. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s that tattooing started to take off amongst the general public when a slew of iconic artists began making waves in the tattoo community. Even then, the perception of a class division on the acceptability of tattoos was a recurring media theme in Britain. Successive generations of journalists pronounced them newly fashionable and no longer just for those living on the margins.

The invention of the tattoo machine allowed more intricate designs to be inked, giving artists more control and decreasing their clients’ pain. It also made the process faster and, consequently, more affordable. Artists like the legendary Sailor Jerry, who worked out of a shop in Honolulu before and after the Second World War, began modernizing the profession. Sailor Jerry introduced new colored pigments, single-use needles, and an autoclave to sterilize equipment. He wasn’t alone, and a fresh wave of artists made tattooing more accessible by making the process safer and their clients more comfortable.

In 1969, the UK’s House of Lords debated a bill to ban the tattooing of minors. This was because it had become trendy with the youth but was still associated with criminals. It was noted that forty percent of young criminals had tattoos, and this was said to encourage identification with criminal groups. However, two peers, Lord Teynham and the Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair rose to object that they had been tattooed as youngsters with no ill effects. Nevertheless, the bill was passed into law and is still in force today, albeit rarely enforced. Since then, tattoos have become socially acceptable, and the 1980s and 1990s saw a growth in tattooing that established the art form as a bonafide industry.

Today, tattoos are a social norm. What once may have been taboo, eccentric, or outlaw is now part of mainstream global culture. Flaunted by ballers, movie stars, tech billionaires, carpenters, teachers, and doctors, tattooing is here to stay. What started as a tribal ritual has become a personal visual statement, answering a need that taps into an ancient and universal tradition of self-decoration—a tradition now supported by a global industry with revenues of USD 1.75 billion and growing.

Tattoo culture has evolved from markings of cultural and social status to symbols of adornment and fashion. Tattoos today, especially in the West, are predominantly a vehicle for self-expression. However, a legacy remains in many communities that signifies the community’s place in history. The reason for getting a tattoo varies, but their primary purpose has always been to convey a message of great significance through a visible signal.

Edited by Michael Moss