The Role of the East India Company and the British Rule in the Indian Subcontinent

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the ages of imperialism and colonialism were kickstarted by the expansion of European merchant fleets. This was the birth of modern capitalism when sailing ships connected the continents and sparked a race among European nations to discover untapped riches and trading bases around the globe. In their wake, they left significant upheaval trailing across the global economic and political landscape.

At this time, merchant trade enterprises like the English East India Company acted as the agents of empire. The East India Company (EIC). was a trade monopoly that connected Asia and the West. There were similar entities to the East India Company, both British (like the Virginia Company in North America) and non-British (like the Dutch East India Company).

However, the EIC was so successful at amassing riches and power that it ultimately eclipsed its competitors. Its history makes for a great jumping-off point for research on the connections between commerce and colonialism during a pivotal period of global history. As we shall see, calling the EIC a trading company is euphemistic. Trading did take place, but so did brigandry and plunder.

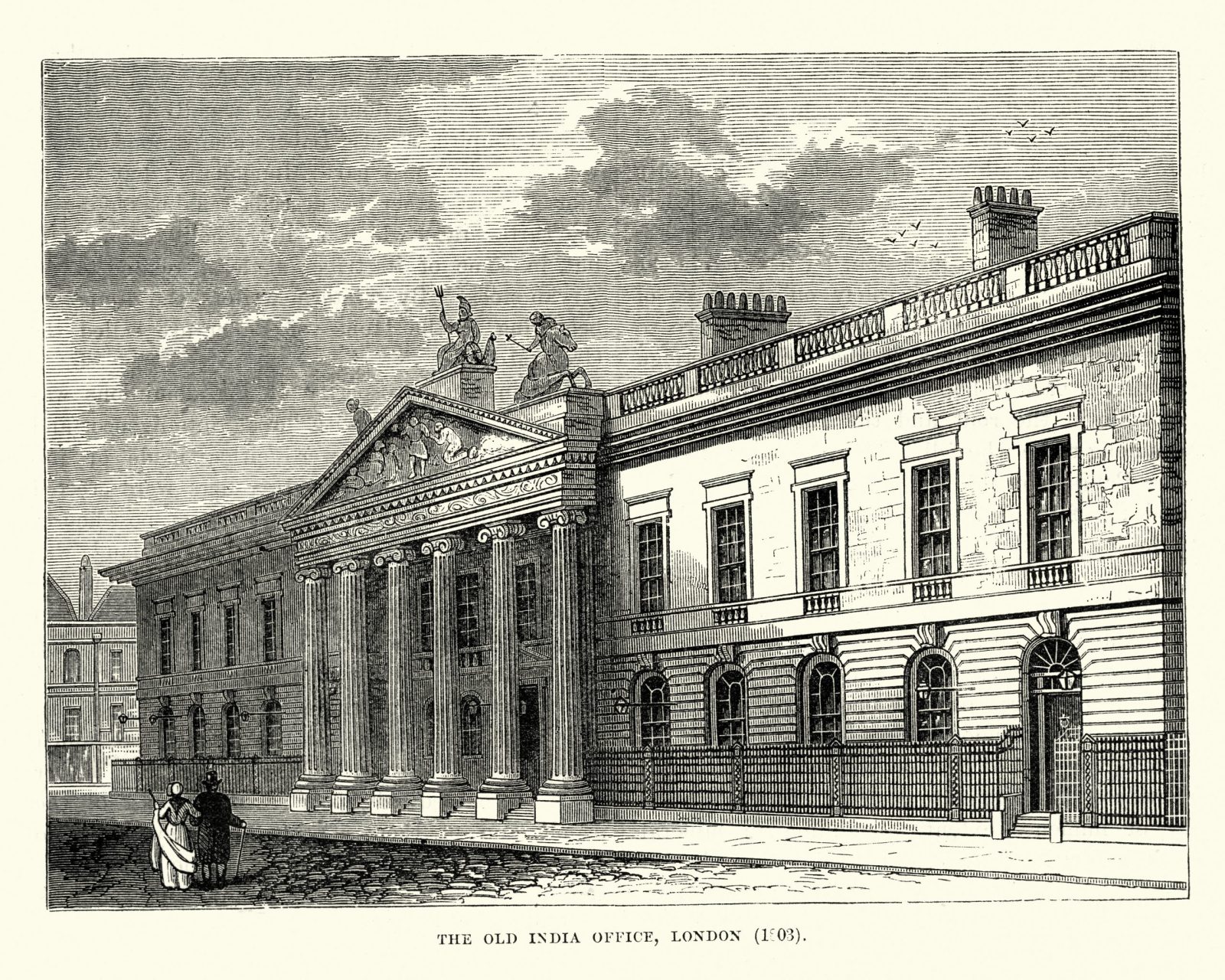

The Establishment and Expansion of the East India Company

In the 16th century, Dutch and Portuguese corporations were making big money off the lucrative spice trade in the Indian Ocean. English merchants grew intrigued by the idea of getting in on the action. They invested in a company and purchased ships. “The Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies” officially obtained a royal charter from Queen Elizabeth l in 1600. They would come to be known as the ‘East India Company,’ and the founders were granted a monopoly of all trade in the Indian sub-continent for 15 years, as decreed by the royal charter.

The EIC was a publicly traded joint-stock corporation owned and managed by individual shareholders. It was one of the first companies to grant its shareholders limited liability. An innovation that gave them some protection. Should the firm fail, shareholders could not lose more than their investment. This was a unique advantage bestowed by the Crown to the EIC. By the late 1800s, limited liability was recognized as a standard part of a corporation’s legal structure. Today limited liability is regarded as foundational to the deployment of capital and modern corporate governance. By reducing risk, limited liability makes raising larger quantities of capital easier.

Throughout its lengthy existence, the EIC provided financial assistance to the English (and later the British) government through loans. It also borrowed money from the government, most notably when the EIC faced bankruptcy in 1772. At times it was challenging to determine where the government stopped and the EIC began. However, the original EIC was not a state-owned business in the sense that the term is often used today. The state did not own shares of the company and was formally involved in its governance only in the latter years of its existence.

While the state did not initially own shares in the EIC nor control the actions of the EIC, it was nonetheless able to exert a significant influence over the company’s performance. In addition to utilizing military and foreign policy to achieve favorable commercial outcomes, the British government also indirectly controlled the EIC by exerting its right to examine and renew the charter. This allowed the government to exert substantial indirect influence on the EIC. The complex interaction between those who give and those who receive patronage is essential to understanding much of the EIC’s history.

At the beginning of its existence, the EIC competed head-on with its Dutch equivalent, the Dutch East India Company. This fierce competition was frequently extended to combat between the two companies or between the mercenaries employed by the two companies. The comparisons and differences between them are illuminating. If we limit our discussion to the spice trade in the East Indies during this period, we find that the EIC placed second in sales volume and earnings behind its Dutch competitor. Despite this, by 1611, the EIC established a foothold in India, on the Bay of Bengal, while boosting global commerce. In 1615 the company established a second base in Surat, further cementing its presence in India.

The 18th century was a time of political and economic instability in the Indian subcontinent as the enormous Mughal Empire was disintegrating. This led to rivalries among those who wished to succeed to the Mughal throne amidst efforts by competing rulers to extend their realms. As a result of the British and French firms’ employment of their respective military forces to defend and develop their interests, these companies became influential deciding factors in conflicts that included Indian monarchs. In other periods, they employed military force to expand their spheres of control and install Indian kings who would serve their interests. There were many wars that the British East India Company fought before finally coming out on top. In 1757, it took control of Bengal with the assistance of 20,000 Indian mercenaries, and by the end of the 18th century, it had expanded to become a kind of shadow British Empire. Thus, the disintegration of the Mughal Empire corresponded with the consolidation of British power.

Royal Consent Leads to Factories

The EIC first arrived in India as spice merchants. At the time, spices were particularly valuable in Europe since they were used to preserve meat and for medicinal purposes. In addition, EIC commerce centered on the exchange of silk, cotton, indigo dye, tea, and opium. In 1613, the Mughal emperor Jahangir awarded Captain William Hawkins a farman (certificate of royal permission), clearing the way for the English to build a factory in Surat. Thomas Roe, the British Ambassador to James I, obtained an imperial farman from Jahangir in 1615, allowing him to build factories and trade across the Mughal Empire. The term ‘factory’ is also euphemistic; these establishments were fortified trading posts.

The company’s impact quickly surpassed that of the other European trading companies once the Vijayanagara Empire permitted the establishment of a factory in Madras. British settlements arose in the three main commercial centers of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay. Additionally, several trade stations were established throughout the whole length of India’s eastern and western shores.

Political Interference: A Step Towards Establishing British Rule

The early members of the British EIC concluded that India was an extensive collection of regional kingdoms, and they desired to centralize the country’s resources. As a result, the corporation began to interfere in the political process in India, and they began to see a gradual improvement in their financial situation. In 1757, the British delivered India its most devastating blow with the death of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, at Robert Clive’s hands in the famous battle of Plassey.

After that, in 1764, there occurred the Battle of Buxar, in which Captain Munro was victorious against the combined armies of King Shah Alam II of the Mughal Empire, Shujauddula of Awadh, and Mir Qasim of Bengal.

The EIC began transitioning from a trade corporation to a governing company in an unhurried yet resolute manner. The EIC continued to amass more and more power until it was finally abolished in 1858, after the outbreak of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. At that time, the British Crown assumed direct control of India, inaugurating the period of official British administration there.

Adoption of English Law

Adding a significant status to Bentham’s liberal ideas about law and his integrity for egalitarian principles, the British formulated some rational laws to ensure order, certainty, and uniformity in Indian social strata. In addition to establishing a sense of legal stability and maintaining the rule of law, these rules were used to put down local rebellions. Under the British occupation of India, the Mughal Court and much of the warrior elite were abolished. The EIC eliminated many local feudal landowners and formed a bureaucracy modeled after the British system. Under this system, the new aristocracy tended to live in the same manner as the British. The British brought with them the English language and its culture, literature, and philosophical underpinnings to consolidate their hold on power. To get ahead in this rapidly changing India, it was undeniably advantageous to be an Anglophile.

British Law

Creating Divisions in Society:

The British administration adopted the divide-and-rule strategy to foment hostility between Hindus and Muslims. Dividing Indians along religious lines as part of this strategy contributed to the upheaval that resulted in the deaths and displacement of millions of people and the destruction of vital infrastructure during Partition in 1947. The British were aware that India was home to a wide variety of religious and ethnic communities, and they knew that it was advantageous to incite strife between Hindus and Muslims, as well as between the ordinary people and the princes, in order to govern and exploit the entire continent. Moreover, inciting strife between different Hindu castes deepened existing divides and exacerbated social stratification within the Hindu religion. For instance, the British administration utilized propaganda to undermine the landed property requirements of the Hindu constitution and discredit the rightful rule of the Muslim Tipu Sultan, who had established his Muslim kingdom in Mysore. He remains controversial, lauded by some as a freedom fighter and decried by others as a religious bigot. Nevertheless, Tipu Sultan fought the British in three different wars before dying heroically during the Siege of Seringapatam in 1799, with his men outnumbered two to one by EIC troops.

Introduction of the British Education System

Because it facilitates ‘the transmission of information across generations,’ education significantly impacts a nation’s culture. Before the entrance of the British, India’s educational system was on a local scale but was very well structured. Hindu children were educated in pathshalas and tols, while Muslim students attended madrasas and maktabs for their education. Arabic, ancient Persian, and Sanskrit manuscripts, theology, logical reasoning, law, algebraical mathematics, philosophy, medicine, and astrology were among the subjects taught to youngsters at these schools. However, the British government decided to replace these religious-based educational systems with its own, partly at the urging of British evangelists. Standardizing education by introducing a British-style curriculum would, in theory, give the British greater control. In practice, at this time, only the well-to-do, whether Indian or British, were receiving education to any meaningful degree. Nevertheless, by imposing their brand of education, starting in 1835, the British confirmed that they regarded the colonization of India as a multi-generational endeavor.

The Foundation of Empire

The EIC may have been founded as a trading company but bore only a passing resemblance to one. It evolved into something more akin to a piratical nation-state with a voracious treasury and little qualms about using its private army and navy to fill it. For young men with a particular skill set, the EIC offered a chance for adventure, glory, and riches beyond compare. Driven by these ambitious interlopers, the company would conquer large swathes of the Indian sub-continent and set the scene for an official British colonial administration. In many ways, the East India Company was the cornerstone of the British Empire. An empire that would fondly regard India as ‘the jewel in the crown.’