Prehistoric Life Hacks: Tools and Fire

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

Daily life can be both demanding and exhausting. We often find ourselves in danger of suffering from Burnout. Believe it or not, this has always been the case. Ever since our ancestors first stood upright, humans have looked for ways to save time and energy. We constantly seek more effortless ways to get more done within the limited hours of the day. To this end, we look for shortcuts. We may also creatively repurpose resources to serve our situations. All this is done to accomplish more while exuding as little of our precious energy as possible. In short, if we can find a crutch, we will lean on it.

Today, we refer to these tactics as “life hacks.” Binder clips can help tidy up cables, bread clips make handy cord labels, a hair straightener quickly irons collars, and frozen grapes cool wine sans dilution. Also, a dustpan to fill a container from a sink, a rubber band for a stripped screw, or a dry tea bag to freshen shoes. Meanwhile, people in developing nations with limited resources have taken to repurposing and reinventing to another level altogether. Again, this is nothing new.

The World of Early Hunter-Gatherers

Around 200,000-300,000 years ago, Homo sapiens emerged in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley. Their “To-do list” was relatively brief. 1. Get food. 2. Don’t get eaten. 3. Stay warm and get some sleep. 4. If time permits, ensure the rest of the community stays alive. This short list may seem straightforward but don’t be fooled. In the world our early ancestors knew, this handful of tasks would take up all their time and wear them out fast. With only their hands and feet to work with, humans had to get very creative very quickly.

Getting food (while not becoming food)

Early humans relied on hunting and foraging for sustenance, a lifestyle still practiced in some corners of the world. Mobility was vital in prehistoric times, and early humans relentlessly pursued their food sources to avoid starvation. Caloric intake, therefore, was paramount. Unlike today, gaining body fat was a sign of success for hunter-gatherers. They expended significant energy, around 3000 calories a day. This lifestyle, coupled with limited medical care and travel on foot, underscored the importance of efficient calorie acquisition. Our ancestors’ survival depended on securing enough food, especially meat, to sustain them.

Scholars believe that men typically assumed the role of hunters, necessitated by childcare demands and the need for stealth. After all, the “quiet game” only works for so long with young children. Also, everyone in the hunting party needed to keep up! Persistence hunting is a tactic unique to humans. One of humanity’s significant bipedal advantages in this situation is that we are built for cross-country! Homo Sapiens are physically able to run steadily for long distances over long periods. Humans also cool themselves by sweating through the pores of their skin, not by panting through the mouth. Theoretically, a hunter could wear their sprinting prey down over a long chase.

However, the final kill required finesse and minimal calorie expenditure, which posed a significant challenge. And if one did find something, how might they take it down the animal with only their hands and feet? Not only could that be dangerous, but it would burn an abundance of calories for what might equate to a small payoff.

Women probably most commonly undertook the gathering, a more reliable yet labor-intensive method of finding sustenance. Foraging for berries and nuts while safeguarding infants demanded vigilance and physical exertion. Climbing trees for high-hanging fruits was fraught with danger, with any injury potentially fatal without medical care. Not to mention that they had to keep an eye on the kids, too.

As if all this wasn’t challenging enough, fossil evidence suggests early humans were often in danger of becoming prey themselves. Humans navigated a perilous world from Africa’s dangerous fauna to Australia’s giant reptiles and the ice-age predators of the Americas’. Giant birds added another layer of danger all over the globe.

Life for our ancestors was a delicate balancing act. Survival often hinged on ingenuity and sheer determination. Anything to give these prehistoric societies an advantage was a welcome addition. Life hacks were our saving grace.

Life hacks that hack!

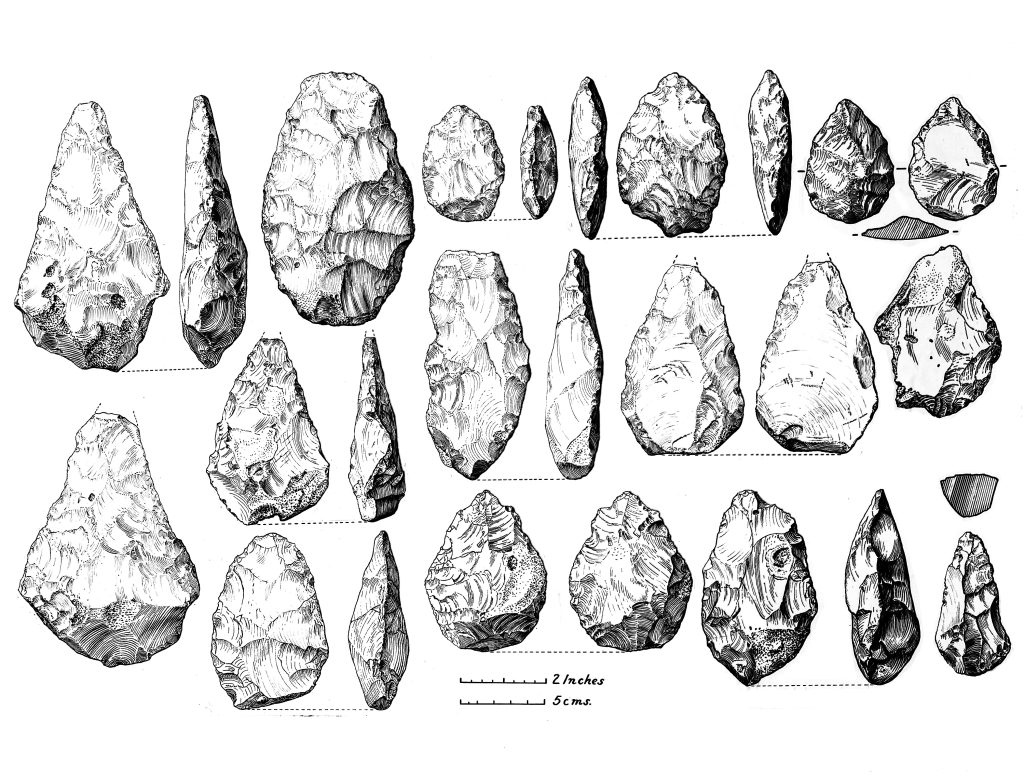

Tools were the earliest manifestations of our tendency to repurpose everyday objects, a precursor to what we now call “life hacks.” Homo habilis and Neanderthals were among the first to engage in this practice, starting with the crafting of sharp-edged rocks. Among the earliest discovered tools are Lomekwian artifacts, dating back potentially as far as 3.3 million years ago. These large stones, with jagged edges facing upwards, allowed for tasks like cutting meat, bone, and wood while seated, conserving energy. However, their size made them impractical for mobility.

Oldowan tools, dating to around 2.5 million years ago, were more prevalent. They were crafted by striking one stone against another to create a sharp edge and were easier to transport. Despite their simplicity, these tools were instrumental in butchering meat and bones, with their widespread use indicating their effectiveness.

Acheulean tools, appearing around 1.76 million years ago, represented a significant advancement. Hand-axes with flaked edges were found across Africa, Europe, and southern Asia, showcasing uniformity in design. These versatile tools served multiple purposes like a prehistoric Swiss army knife.

Flaking techniques evolved, refining blade patterns and shapes. Handles, or “shafts,” were added around 40-70,000 years ago through hafting, connecting stone blades to wood or bone handles with tar. This innovation reduced user strain, allowing for more efficient tool usage. Early hunter-gatherers likely benefited from these advancements, experiencing less physical strain when using compound tools like hand axes and hammers. In the same way contemporary artisans grip tool shafts lower to reduce strain, our ancestors optimized their tool usage to conserve energy and maximize efficiency.

Another example of hafted compound tools is spears, and hunting was only improved by their introduction. This lengthy weapon may be thrust or thrown by its user, making the final struggle less risky. Once the prey was chased down and exhausted, the death blow could be dealt with more space between hunter and prey.

An exciting elaboration came with introducing the atlatl, or “spear thrower.” This accessory component was invented about 21,000-17,000 years ago. A 5-foot-long spear (dart) could be as fast as 80 or 90 miles per hour with an accuracy of 10-30 meters (30 -90 feet), increasing the necessary distance between hunter and prey. The atlatl was an invention so good that it was used by people of the Stone Age from Europe to Australia and eventually Central and South America.

As many vegans and vegetarians have pointed out, the spear’s use was not limited to hunting animals. The long shaft with the sharp, rigid point on the end makes it an equally good tool for picking high-hanging fruit off the branches of tall trees. Therefore, while the plant-to-meat ratio in the Stone Age diet is still being debated, one can’t deny that the gathering aspect of Stone Age life was undoubtedly made easier with the introduction of the spear. It’s amazing how a concept as simple as a long stick with a sharp, pointed stone on end can improve everyone’s day in a hunter-gatherer world. these tools can be defensive or offensive. Sorry predators!

Even more hacks

Blades such as axes and spearheads also made it possible to create. Unlike a spearhead or axe blade, sharp stone blades allowed for creative manipulation of other everyday resources to craft even more time- and energy-saving life hacks. For example, strip some long strands of ordinary tree bark, and you have all kinds of potential uses! Weave them together in a mesh pattern or, better yet, twine them together, and you’ve got . . . well . . . twine! Baskets and other containers could now be made. As such, the gathering became a much more fruitful endeavor.

We didn’t start the fire, but we gathered it

Before fire, there were few options beyond simply huddling together to stay warm. Some humans even seem to have hibernated underground for months during the winter. In the Spanish cavern of Atapuerca, the 400,000-year-old fossilized remains of several dozen early humans have been found huddled together. The state of these skeletal remains suggests that they were in a state of hibernation and not for the first time. Still, seeing how it was their last, it’s also easy to see why we don’t do this anymore.

Lightning and other sporadic natural phenomena likely introduced humans to fire as it set the landscape ablaze. A widespread fire could have been dangerous and devastating for a Paleolithic community, but there was no denying that in a cold stone age, the fire seemed like it might be nice in small doses. Since fire itself doesn’t fossilize or preserve in any way, it is hard to trace man’s journey with it. Still, our best guess is that we started by gathering fire.

Archeological sites such as Koobi Fora in Kenya hint at fire circles being used up 1.6 million years ago, far before methods of creating fire were believed to have been possible. Reddish-orange patches of baked earth indented into the ground led researchers to conclude that some of our ancestors likely took burning branches from a pre-existing natural occurrence and made themselves some campfires.

Since fire remained unpredictable for a long time afterward, one could only hope to continue feeding it constantly to keep it going indefinitely. Needless to say, this was probably a pain in the neck. And no one wanted to be the fool who let the fire go out. Our ancestors probably spent much time pondering how we might make this toasty, orange resource ourselves.

Who made fire, and how?

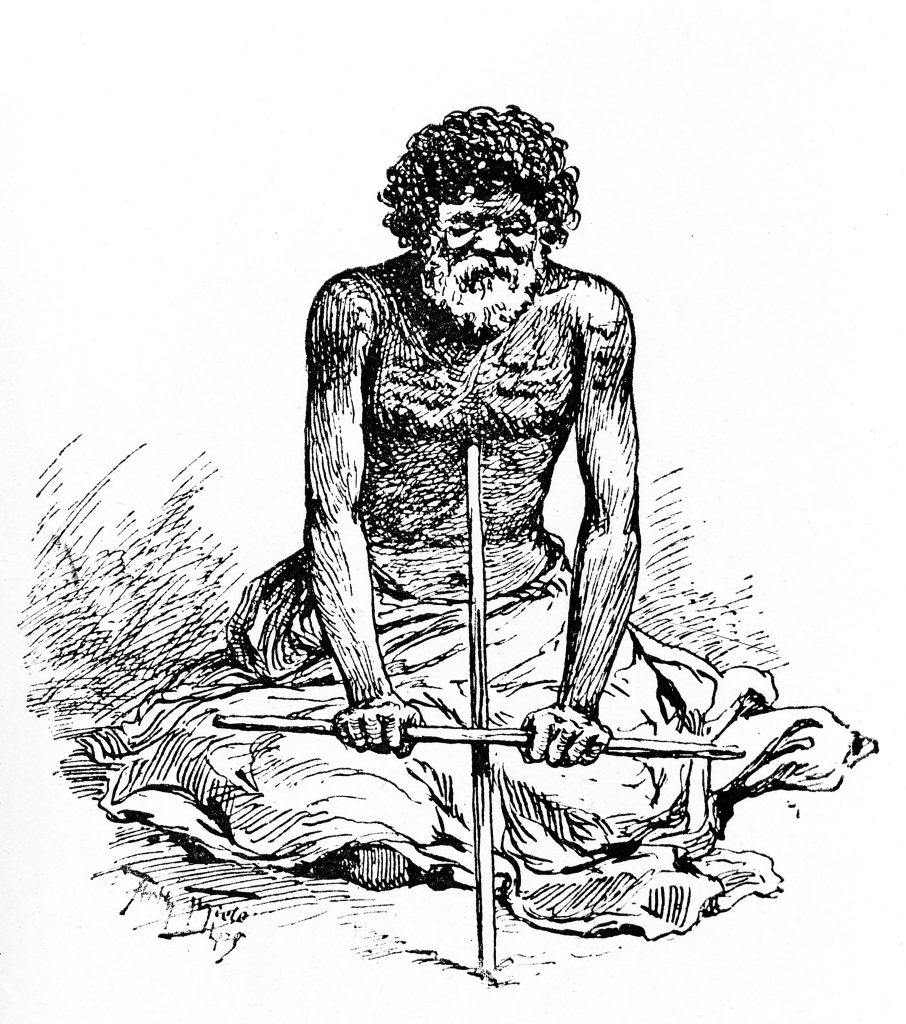

As mentioned, women foraged, tended to the youngest children, and generally kept camp while men went out hunting. Since this is where the fires were, it likely fell to the women of early hunter-gatherer tribes to sustain the burning. As if they needed anything else to worry about! This is why many scholars assume it was a woman who first conceptualized the friction method of fire-making by rubbing sticks together (presumably fueled by her pent-up frustration!) near some combustible material like dry grass.

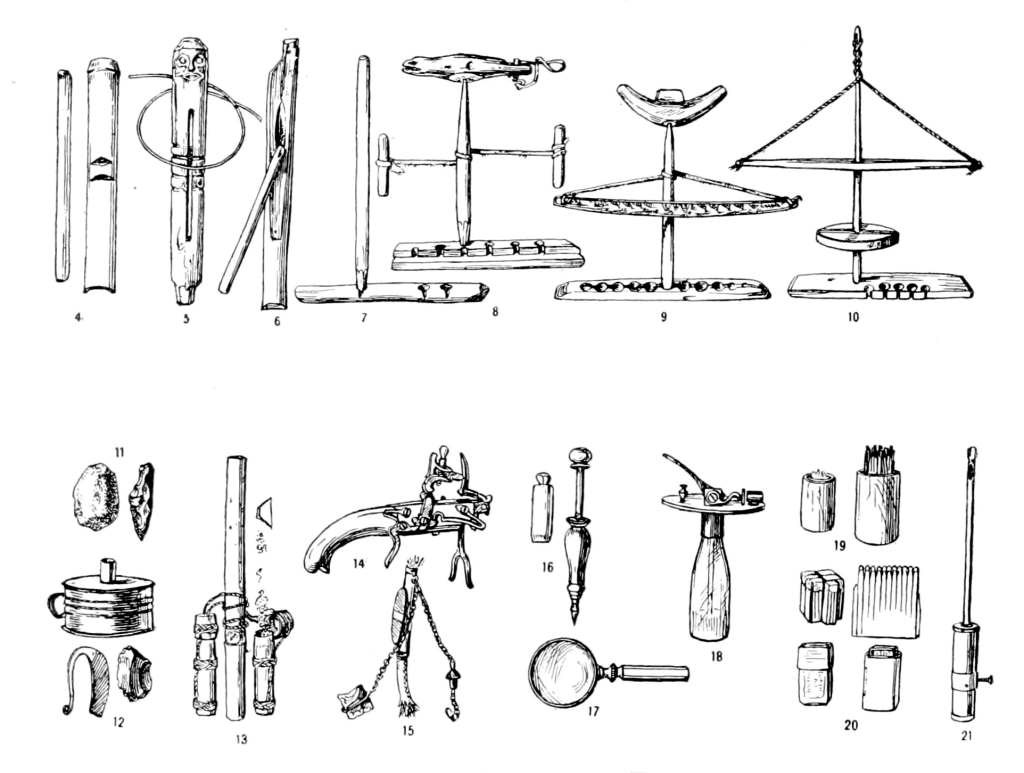

At some point, the link between friction and combustion became obvious. So, once again, the best possible tools were devised. The hand drill, bow drill, pump drill, fire plow, and fire saw were all built upon the general principle of the friction method to make friction-to-fire happen faster and with less energy.

The results of this new life hack cannot be understated. The addition of fire-on-demand increased man’s chances of survival and extended the day for several hours by providing heat and light in the absence of the sun. This allowance for nocturnal productive or recreational activities was a true gift.

The fire was also crucial as a defensive element against predators. It may possibly even predate tools and weapons, but it is hard to say. Regardless, nothing compares to the rich legacy of cooking brought about by humanity’s ability to create fire.

The human legacy of cooked food

Before the fire development. Eating raw meat and uncooked vegetation can take its share of time and energy. A study by Harvard University hypothesizes that anywhere from 40-50% of the day might have been devoted simply to chewing. Cooking reduced the toughness of the food, which helped immensely. It also breaks down toxins in the food, making it easier and safer to digest.

Cooking food also reshaped our faces. With the advent of cooked meals, our teeth gradually reduced in size, our facial structure evolved, and remarkably, our brains expanded. Richard Wrangham, in his seminal work “Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human,” albeit with less ideological fervor.

Cooking, fueled by the mastery of fire-making, catalyzed profound changes both within us and in our external environment, sculpting the very essence of homo sapiens. Today, we continue to leverage this ancient innovation, perhaps by preparing meals in bulk on a leisurely Sunday to sustain us through the week—a modern-day life hack built upon a life hack.

Hacking toward the future

This instinct to work smarter and not harder got humanity to where it is today. Civilizations are built upon hundreds of thousands of years of life hacks. One might even say these life hacks are what make us human. So, we continue to employ the principles of efficiency and problem-solving inherited from our ancient predecessors. Who knows where we will hack our way to next?